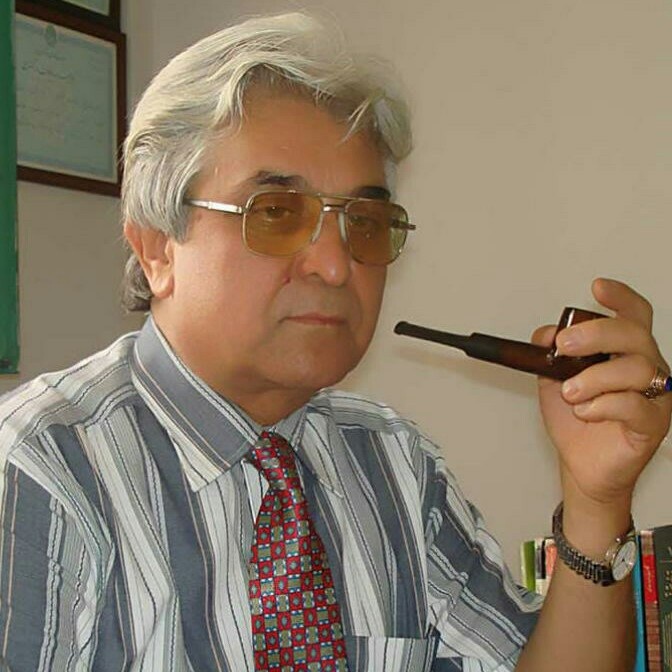

Mohammad Seifzadeh, the prominent Iranian human rights lawyer

April 14, 2016— Prisoners Face Denial of Medical Care, Refusal to Transfer Inmates to Hospital despite Life Threatening Illness, Solitary Confinement Aimed at Extracting False Confessions, Poor Nutrition, Denial of Family Visits

Mohammad Seifzadeh, the prominent Iranian human rights lawyer who for years defended political prisoners in Iran and railed against the inhumane conditions of their incarceration, was freed on March 10, 2016 after serving his own five-year prison sentence, and spoke at length about the harsh conditions he experienced first-hand as a political prisoner.

Seifzadeh described the denial of medical care and critically needed hospitalization, white torture (sensory deprivation and isolation), poor nutrition, unsanitary quarters, insufficient fresh air, and denial of family visits in an extended interview with the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran. These conditions directly violate Iran’s own laws and State Prison Procedures.

“Seifzadeh’s imprisonment for defending human rights in Iran was a travesty of justice to begin with,” said Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran, “and the conditions he and other political prisoners face are an affront to the rule of law and the most minimal standards of humane treatment.”

“President Rouhani needs to defend his citizens and confront the Judiciary over these violations,” added Ghaemi.

Seifzadeh, who was imprisoned for his work defending political prisoners in Iran, also revealed that during his detention in Ward 209 of Evin Prison in Tehran, which is controlled by the Intelligence Ministry, he was put under extreme pressure to falsely incriminate his former colleague, Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Shirin Ebadi. Seifzadeh and Ebadi were founding members of the banned Defenders of Human Rights Center.

“When that was going on, I was in solitary confinement and my blood pressure shot up…It was out of control. They took me to the General Ward 350 and I had a stroke but they didn’t say it was a stroke,” Seifzadeh told the Campaign.

Solitary confinement is a common tactic used in Iran to increase psychological pressure on a prisoner to extract a false confession, which is then used as evidence to convict.

“They didn’t give me any treatment. They didn’t even take me to the infirmary. My hands and feet gradually went numb. My hearing and vision weakened. I fell on the ground when I tried to stand,” he said. “Finally, when the official medical commission looked into [my case] much later in March 2016, it said I had suffered a stroke.”

In October 2010, Seifzadeh was sentenced to nine years in prison and banned from practicing law for 10 years for “acting against national security through establishing the Defenders of Human Rights Center.” He was arrested while on bail on April 6, 2011 for allegedly attempting to leave the country.

The Appeals Court reduced Seifzadeh’s sentence to two years in prison, but while he was serving time he was sentenced to an additional six years for writing open letters and signing political statements with other prisoners of conscience.

Seifzadeh was released after serving five years, under Article 134 of Iran’s Penal Code, which allows prisoners charged with multiple offences to only serve the maximum sentence assigned for their most serious offense.

The human rights lawyer told the Campaign that doctors from one of Tehran’s hospitals for cardiology had warned that he was at serious risk for a deadly heart attack or stroke if he remained in prison, but the authorities ignored the warning.

“I had one medical problem after the other, and eventually they illegally exiled me to Rajaee Shahr Prison [in Karaj, west of Tehran] without a judicial order,” he said.

Political prisoners in Iran are singled out for harsh treatment, which often includes denial of medical care.

“I had breathing problems while sleeping and also while I was awake,” he said. “They took me to Baharloo Hospital and I was connected to a machine, which showed that during the night I briefly stopped breathing nine times and woke up 13 times, therefore I could not have any sort of deep sleep all night.”

“I paid all the hospital bills myself,” added Seifzadeh. “It would be unthinkable for the prison authorities or the health system to pay a prisoner’s expenses. There’s no budget set aside for it. If you don’t pay the bills, you won’t get treatment on time and you don’t know if you’ll live or die.”

“Every prisoner [sent to the hospital] has three agents to watch him and is responsible for their expenses, such as meals, too,” he added.

“The clinic did not have medicines to treat anything worse than a cold, let alone high blood pressure,” he told the Campaign. “Bad nutrition and lack of vitamins weakened the prisoners.”

“Fruits and vegetables are non-existent,” continued Seifzadeh. “Some of us prepared our own food. We gave a list of things we needed and they would buy it for us from outside at our own expense. But there were also those who only ate prison food,” he said. “Two days a week there was stew and on other days it was only rice and soybean oil, which was greasy and unhealthy.”

“The cells had no ventilation,” Seifzadeh said. “In Evin Prison, the cell doors opened at a quarter to seven in the morning and you could take in fresh air until sunset, but in Rajaee Shahr we could only stay outside for three hours.”

He added that “the prison was not in any condition to hold that many prisoners,” and that they “used sub-standard detergents and as a result many of the prisoners developed skin allergies.”

Seifzadeh also told the Campaign that the interference waves aimed at disrupting mobile phones from functioning inside the prison were so strong that they caused many prisoners to suffer from headaches and nausea. “I think it was a factor in my strokes as well,” he said.

The prisoners’ living quarters would also be subjected to occasional raids. “[In Rajaee Shahr Prison] they would conduct illegal searches to look for mobile phones…Having a mobile phone is not illegal, but they don’t want prisoners to give interviews to anyone outside the prison, so they would grab the mobiles,” he said.

“Often times, both the prisoner and his family suffer injustice,” said Seifzadeh. “In our case, [political prisoners] were not only arrested illegally, but also subjected to unfair trials.”

He noted the prisoners in Rajaee Shahr Prison were only allowed one 20-minute family visit per month. However, Seifzadeh was denied family visits for most of his own prison term, keeping with the harsher conditions that political prisoners are subjected to in Iran.

“Many of the Rajaee Shahr and Evin Prison inmates are from different cities. They should be sent to prisons near their families,” Seifzadeh said. “There were several instances when family members got into road accidents, and even died, on their way to prison visits.”

Hundreds of political prisoners remain in Iranian jails, some dating back to the widely disputed 2009 presidential election in Iran that ended with a violent state crackdown on peaceful protestors. Many Iranians have urged Rouhani to follow through on his presidential campaign promise of freeing political prisoners.

Follow the Campaign on Facebook and Twitter

For the latest human rights developments in Iran visit the Campaign’s website

For interviews, contact:

Hadi Ghaemi at +1-917-669-5996, hadighaemi@iranhumanrights.org